Originally published on the author’s private blog.

I like the Rust programming language, and so I tried to to make it a popular language in Avast, where I work. For some time I gave presentations, made workshops and generally tied to raise the awareness of it here.

Nevertheless, for the venue to be successful, I needed an actual project where Rust would be a good match and the management could be persuaded it was a good idea to try it on. Avast is open to new technologies, but only if they make sense, not just as an excuse to play with them.

The project

So there’s this service, called urlinfo. It’s an old piece of software. Every company that is a year old has a code base that’s two years old. Avast is 31 years old. Today, most of Avast’s backend software is written in Scala. And some Python and Perl and C# and… whatever else too. But mostly Scala. This thing is in Java, because it predates Scala. Well, probably not the language itself, but definitely its use in Avast. You can give it an URL and it’d look into its data and tell you if it’s hosting malware or phishing or if it’s interesting in some other way. This service is used by many of Avast’s solutions, such as the browser extension.

My team’s project, Avast Omni, would become another (indirect) user of that service. We aim at ”bigger embedded“ ‒ home routers, raspberry-style devices and the like. It’s supposed to protect other devices on the network level. With clever tricks you can fit a lot of functionality into such a device, but there are limits and this URL database simply doesn’t fit. So for some things, the device asks the cloud (read: Avast servers) for assistance. That assistance includes other analyses than just consulting the large urlinfo blacklist, but we are not going to be talking about these right now.

For our use case, latency is important. We want to impact the user’s browsing experience as little as possible, so waiting a long time for the server response and delaying the packets for that long is a no-go. If the device doesn’t get an answer from the server in time, it gives up waiting and decides based on its own limited best judgement. That internal timeout includes the network communication with the server and the devices will live in our customers’ homes, often with questionable connectivity. The time limit is not very generous.

How do we deal with that short time? In several ways.The client keeps a persistent connection to the backend server. We don’t want to waste the precious time with TCP handshake and TLS negotiation when time’s ticking ‒ just one packet there and one back.

The client actively seeks to find the closest server available, but for that to have some reasonable effect we need some of the servers to be physically close to each customer. We need servers scattered throughout the world, which means having a lot of them at different data centers.

The server needs to answer fast.

The urlinfo service was giving us trouble in these areas. It uses about 16GB of RAM. If you want to have a server close to just about anyone, you have to buy VM instances from various providers and you’re going to be billed based on how much RAM you want them to have. But that’s just money.

More importantly, the garbage collector stops the application for several hundreds of milliseconds to scan that 16GB. That just plain out doesn’t fit in our limit. Of course we didn’t know until our end-to-end test began to fail and investigated where the delay come from.

When I saw the reason for our test failures in a Slack conversation, I reacted with this little :crab: icon, followed by a question-mark icon (by that time it was enough to indicate a “would this be a good place to try out Rust on?“ from me). Partly in a half-joke, partly because it was part of the habit, except my boss took it seriously and gave it a thought.

And it turned out not to be a bad idea. Some colleagues tried to tune the JVM GC in the old service, to limited effect. Slimming the memory consumption down significantly would be a rewrite of the whole thing anyway and nobody wanted to touch the old code base.

It’s a back-end service, therefore it is easily fixable if anything goes wrong (unlike code running at people’s homes), so trying Rust out there is lower risk. Furthermore, we needed only part of the functionality of the old service, which was another way to slim it down.

So the urlite project was born. We worked on it in a team of two (both of us having it as a secondary project), the other person a volunteer from the group of people who visit the workshops. We are trying to make more people interested, some other projects are watching it if it could be useful for them.

Difficulties

As I wrote earlier, all the infrastructure is expecting JVM applications. If you want to start a new project in Scala, you take a template, click two buttons in Teamcity (our CI server), magic happens, and you have the whole pipeline to compile it, test it, deploy it, etc. You just specify which servers it should be deployed to, give it a configuration file and everything is ready, including logs getting to the right places, metrics being available in the internal Graphana instance, the service being monitored with emails about its health routed to you, everything.

We had to do most of that manually with Rust. The metrics format used in JVM applications is not available in Rust. The internal deployment tool creates -noarch packages (let’s hope nobody buys an Arm server any time soon) and runs the thing under JVM. Teamcity still tries to point out the ehm relevant places if tests fail thinking it should look like an output from the Java tests. Some colleagues still ask why another language is needed when everything else is in Scala.

None of this was an impossible problem, nevertheless, it was a lot of work. Hopefully, next time, there’ll be less of it or we’ll at least know what to do. On the other hand, part of that work is public as part of various open-source libraries. We reported number of issues and sent several pull requests. Some of my own libraries got more testing and in case of spirit, a bigger API overhaul as a result of that testing. While the core knowhow and the actual application needs to stay closed, doing the rest in public actually saves us future effort ‒ both with maintaining it and with being able to pull directly from crates.io in our next project. General development in Rust feels slower than in Scala (according to the colleague, I don’t know Scala so I’d be definitely faster in Rust).

The results

It’s still not under heavy load yet, it’s being put into production slowly. But preliminary testing suggests the results are good. The processing times are very consistent and around 1ms. The memory usage is under 500MiB of RAM most of the time, slightly more during an update of the data sources (there’s a short time we have both the old and the new one loaded). Startup time to fully operational state is just a few seconds ‒ less than what the JVM takes to boot and load the urlinfo application without any data in it.

How is this possible? Part of the story is that Rust doesn’t have the garbage collector ‒ or, as pointed out, has a static compile-time garbage collector. Garbage collectors waste some CPU (which is not the issue here), but also memory and introduce latencies that are really hard to control and compensate for.

But there’s another part. Rust attracts people who like challenges. So while things like integrations into corporate systems (sentry, logging systems, metrics) feel immature, there are loads of libraries for tackling the hard problems. I’m not listing all the libraries we used, but having them available and ready to be used with minimal effort made the task not only possible, but actually enjoyable. I’ll point to just one of them, the fst, which allows us to have the data in RAM compressed while still searchable.

Besides having the data in a format that is both compressed and searchable at the same time and having the hot-path lockfree (well, there might be a lock somewhere in the memory allocator, we haven’t made the hot path allocation free yet), we prepare the data images on a central server so all the virtual machines doing the serving don’t have to.

When testing and deploying it, we have seen surprisingly small number of bugs ‒ as little of them that it makes me nervous some must be hiding somewhere we haven’t looked.

Some other projects start to consider using the new urlite service too ‒ for example the VPN products couldn’t use the urlinfo for similar reasons as we but they think urlite would work for them, thanks to the lower memory consumption and consistent latencies.

A little allocator mystery

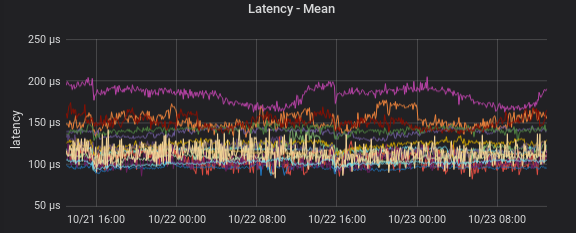

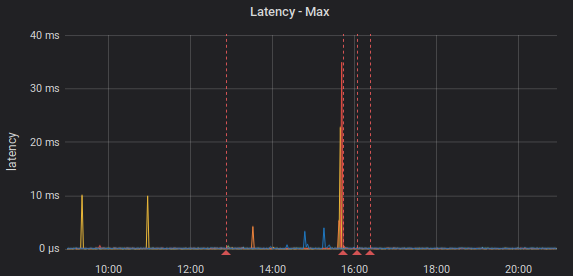

We were also investigating a little mystery. The usual processing latency (without external communication) is ~200μs. However, from time to time, there would be a latency spike of several milliseconds. It was happening even when not under any particular load ‒ few requests per second were enough. Not that it would be a serious problem for the use case. Such a spike happened few times a day. But it shouldn’t have been happening and the natural question was if it’s an indication of some more serious problem.

It turned out to be an artifact of how Jemalloc works. During loading of the data, we allocate a lot (or, we did in the previous versions, now it happens on the central server). Then we free a large part of it, and also the previous version of data. Jemalloc keeps the unused memory for a while, but eventually decides it is not going to be used any time soon and returns it to the OS. This returning is supposed to happen gradually. However, because we had more worker threads than queries, the one thread unlucky to be responsible for freeing this memory was idle for large enough time and all that unused memory decayed (that’s the Jemalloc’s term for deciding it is unused for too long) during the inactivity time. Then, the one query that woke the thread was responsible for cleaning all that memory up, which consists of calling a lot of syscalls. Unlike the allocation which happens in a background performance non-critical thread, this hit the query processing.

It also turns out Jemalloc has a knob for exactly this. It can start its own background threads to do these cleanups without disrupting the application. As can be seen in the image (the vertical dashed lines are deployments), this had the desired effect ‒ one line change in Cargo.toml, but discovering this took a long time and some experimentation.

Conclusion

I can’t speak for other people around the project, but for what I see, Rust is less productive in the initial development phase than other languages ‒ part of it is the immature libraries and the internal systems not ready for a non-JVM language with different metrics and logs formats. But part is also that sometimes tweaking the code around the borrow checker just takes some effort, or that very strict types do get in the way (returning 3 alternatives in an impl Trait place, for example). I’m not even talking about the effort to learn it (on the other hand, my attempts to learn Scala didn’t end that well).

On the other hand, it does allow fulfilling the more crazy needs. Pushing the RAM consumption and the latencies down may be just one of them. Being pretty confident about the code working correctly is another.

So as always, choosing Rust as the language brings trade-offs. Sometimes the speed of development is the major factor and then there probably are better languages to pick. But when the problem being solved gets interesting, Rust may come to save the day.