This blog post is based on some testing that I did some time ago. In my team at Avast, we are using Yara to its fullest potential, and even though we are satisfied with this tool overall, we’re constantly working on additional improvements (as mentioned in the previous posts, such as Making YARA better: Authenticode, .NET, Telfhash).

One aspect that we are trying to improve is the scanning speed, as we believe that there is room for improvement. For these reasons, we decided to test some alternatives to reveal different, faster solutions that could be used in a similar fashion as Yara.

There are many pattern-matching engines for regular expressions (for example, a quite nice list of them can be found on Wikipedia). However, not all of them were created for very fast matching or matching of multiple patterns at once. This doesn’t mean that they aren’t useful, but there are differences when matching one pattern in one or few strings and when matching hundreds and thousands of strings in petabytes of data.

In this blog post, we will be taking a look at HyperScan, as it is very fast and can match multiple patterns simultaneously. To be clear, it is not a direct substitute for Yara, but the promising results initiated a project that will be announced very soon. Stay tuned for more information!

Regex Performance Tool

I am far from the first to compare pattern-matching engines – there are plenty of papers and articles online. Still, the one I would like to mention the most is the inspirational article, A comparison of regex engines, written by Sascha Grunert in 2017. He also created a comparison tool that has been extended and updated since then.

For this blog post, I created a PR that is adding Yara to the tests, as I believe that Yara can be easily used outside of the world of malware analyses as well.

I will describe that HyperScan is faster in most cases, but Yara also has quite a nice speed compared to other engines such as Tre, Boost, and others.

Yara

For Yara, the newest version from the upstream repository, version 4.2.0, was used. Yara is probably well known to the readers of this blog, but in short, Yara is a tool written in C and used mostly for malware analyses. So-called rules are used: a description consisting of a set of strings and a boolean expression determining its logic. One example of the rule is the following:

rule The_Adventures_of_Tom_Sawyer

{

strings:

$re = /Tom|Sawyer|Huckleberry|Finn/

condition:

$re

}Code language: CSS (css)This rule searches for any of the well-known names from Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn. The strings can be defined as text strings, regular expressions, and hexadecimal sequences. Condition is a boolean expression, and Yara provides functions for supporting functions, such as searching for mutexes or the number of matches, for a specific string. For matching, the Aho-Corasick automaton is used to search for substrings, and the bytecode engine then confirms the whole match. Additional information can be found in the official documentation.

HyperScan

HyperScan is a project by Intel written in C/C++. Also, as in the case of Yara, the newest version of HyperScan (5.4.0) from the official repository was used.

The project was presented at the 16th USENIX Symposium on Networked Systems Design and Implementation in 2019, where the motivation and the main building blocks of HyperScan were described in detail. The recording is available on the conference website. HyperScan was created with the goal of being able to match large numbers of regular expressions simultaneously while maintaining high performance. It uses hybrid automata techniques and a series of additional optimizations that allow for very fast matching. There are differences between HyperScan and Yara, as I will demonstrate in specific test cases. Additional information can be found in the official documentation.

Specifications

I run tests locally on my VM Ubuntu 20.04 with 4GB of RAM. That means that overall numbers can be much lower using the better conditions, but I aimed to test the engines on limited resources purposely as opposed to the usage in a different situation than what is presented on the blog post and GitHub repository. For that reason, take the times with a grain of salt, and I will also mostly comment on the differences between HyperScan and Yara, rather than whether the numbers are high or low by themselves.

The main idea of the tests remains the same as in the original post. The regular expressions are firstly parsed by engines and compiled into internal representation in both Yara and HyperScan. This step is not measured; we are focusing on the following stage – the matching itself. This step is run five times, after which the lowest time is selected. The tool provides the input file – a copy of Mark Twain’s Huckleberry Finn book.

I run the regular expressions from the original implementation with expectations of the two last expressions. Yara does not support the regular expression \p{Sm} for any mathematical symbol, and the last regular expression (.*?,){13}z is also not supported because Yara does not allow the use of .*?, as these are too general of expressions. Yara is, in general, more cautious about matching general expressions – and it has a good reason for it, as we will see in a moment.

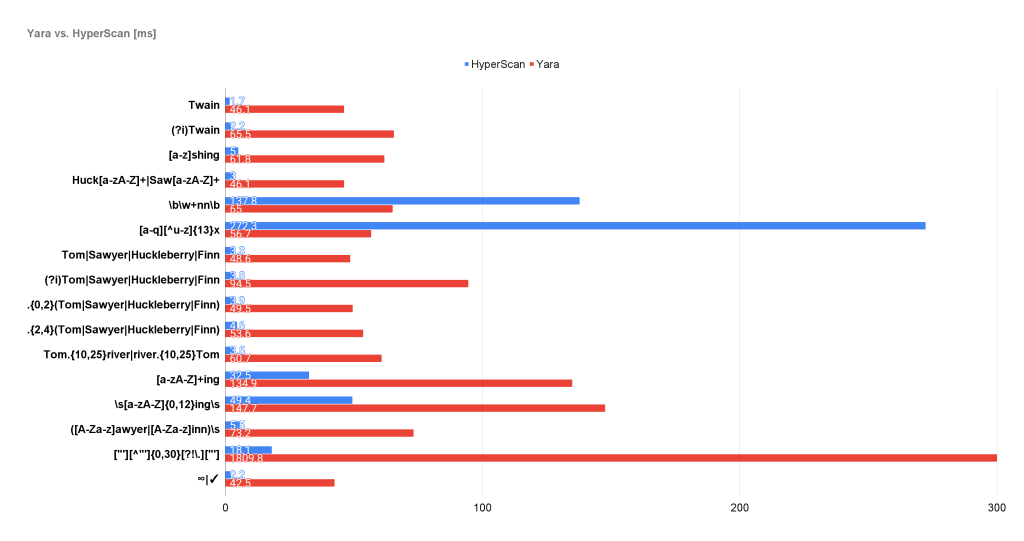

The overall results are the following:

Regex: 'Twain'

HyperScan time: 1.7 ms (+/- 7.6 %), matches: 811

Yara time: 46.1 ms (+/- 3.6 %), matches: 811

Regex: '(?i)Twain'

HyperScan time: 2.2 ms (+/- 5.2 %), matches: 965

Yara time: 65.5 ms (+/- 1.7 %), matches: 965

Regex: '[a-z]shing'

HyperScan time: 5.0 ms (+/- 3.6 %), matches: 1540

Yara time: 61.8 ms (+/- 7.6 %), matches: 1540

Regex: 'Huck[a-zA-Z]+|Saw[a-zA-Z]+'

HyperScan time: 3.0 ms (+/- 3.7 %), matches: 977

Yara time: 46.1 ms (+/- 2.1 %), matches: 262

Regex: '\b\w+nn\b'

HyperScan time: 137.8 ms (+/- 0.9 %), matches: 262

Yara time: 65.0 ms (+/- 13.7 %), matches: 262

Regex: '[a-q][^u-z]{13}x'

HyperScan time: 272.3 ms (+/- 1.2 %), matches: 4094

Yara time: 56.7 ms (+/- 1.1 %), matches: 4094

Regex: 'Tom|Sawyer|Huckleberry|Finn'

HyperScan time: 3.3 ms (+/- 3.2 %), matches: 2598

Yara time: 48.6 ms (+/- 2.1 %), matches: 2598

Regex: '(?i)Tom|Sawyer|Huckleberry|Finn'

HyperScan time: 3.8 ms (+/- 1.8 %), matches: 4152

Yara time: 94.5 ms (+/- 2.6 %), matches: 4152

Regex: '.{0,2}(Tom|Sawyer|Huckleberry|Finn)'

HyperScan time: 3.9 ms (+/- 1.8 %), matches: 2598

Yara time: 49.5 ms (+/- 1.4 %), matches: 6923

Regex: '.{2,4}(Tom|Sawyer|Huckleberry|Finn)'

HyperScan time: 4.6 ms (+/- 2.6 %), matches: 2598

Yara time: 53.6 ms (+/- 1.7 %), matches: 6362

Regex: 'Tom.{10,25}river|river.{10,25}Tom'

HyperScan time: 3.5 ms (+/- 4.0 %), matches: 4

Yara time: 60.7 ms (+/- 5.2 %), matches: 2

Regex: '[a-zA-Z]+ing'

HyperScan time: 32.5 ms (+/- 0.2 %), matches: 78872

Yara time: 134.9 ms (+/- 2.2 %), matches: 335969

Regex: '\s[a-zA-Z]{0,12}ing\s'

HyperScan time: 49.4 ms (+/- 0.8 %), matches: 55640

Yara time: 147.7 ms (+/- 10.6 %), matches: 55640

Regex: '([A-Za-z]awyer|[A-Za-z]inn)\s'

HyperScan time: 5.5 ms (+/- 1.5 %), matches: 209

Yara time: 73.2 ms (+/- 1.5 %), matches: 209

Regex: '["'][^"']{0,30}[?!\.]["']'

HyperScan time: 18.1 ms (+/- 1.4 %), matches: 8898

Yara time: 1809.8 ms (+/- 2.9 %), matches: 8898

Regex: '∞|✓'

HyperScan time: 2.2 ms (+/- 3.9 %), matches: 2

Yara time: 42.5 ms (+/- 0.6 %), matches: 2

Overall:

HyperScan time: 548.7 ms

Yara time: 2856.2 msCode language: PHP (php)Based on these numbers alone, HyperScan was notably faster. However, I would like to go through some specific cases and discuss more differences and reasons behind these numbers.

.{0,2}Tom vs Tom.{0,2}

One of the most notable differences in results is the number of matches that are returned by our engines in the cases where the prefix or suffix does not have a fixed length.

In the first case, .{0,2}(Tom|Sawyer|Huckleberry|Finn), if we have input xxTom, Yara will find all interleaving matches: Tom, xTom, xxTom. This is caused by Aho-Corasick, which will report three potential starts of matches that are all confirmed. HyperScan, on the other hand, will report only the longest match, xxTom, as it is more focusing on the last byte of the match rather than the first one as Yara.

This is also visible in the second example, where the suffix has a variable length. For the regular expression (Tom|Sawyer|Huckleberry|Finn).{0,2} and input Tomxx, Yara would match only the longest match Tomxx, but HyperScan would report all three matches: Tom, Tomx, Tomxx.

These can be seen as minor differences, but it is good to keep in mind when using these tools that what’s fast in one tool can be slower in another due to differing evaluations.

Too General Regular Expressions

Yara also has a known problem when regular expressions are too general. In cases like ["'][^"']{0,30}[?!\.]["'], it is not able to generate substrings for the first phase using the Aho-Corasick, which results in the checking every byte in the input files with a slower regex engine.

Regex: ‘["'][^"']{0,30}[?!\.]["']’

HyperScan time: 18.1 ms

Yara time: 1809.8 msCode language: CSS (css)HyperScan purposely avoids this phase, as it views it as ineffective to match first a substring followed by the whole string again to confirm a match. Instead, they chose a different approach, which is one of the key elements where HyperScan truly shines. Rather than firstly matching a substring, it translates regular expressions into a series of strings and finite automata. With this change, the authors eliminate the redundancy in matching parts of the string twice, and they are also able to create smaller (and thus faster deterministic) automata. The second aspect of improving the scanning speed is scanning accelerations using SIMD operations that leverage the CPU’s compute capability on data parallelism. Both tactics are very effective, as the tests show how the results are vastly different.

Yara can be fast as well

Regex: ‘\b\w+nn\b’

HyperScan time: 137.8 ms

Yara time: 65.0 ms

Regex: ‘[a-q][^u-z]{13}x’

HyperScan time: 272.3 ms

Yara time: 56.7 msTo be fair to Yara, there are two cases in which it was faster than HyperScan. In both of them (\b\w+nn\b, and [a-q][^u-z]{13}x), Yara used the first phase of matching to its advantage. It was firstly looking for nn for the first regular expression and x for the second, and after that, it checked if the rest of the expression also matches. HyperScan has a visible struggle to find all matches. Both of these regular expressions are very commonly present in the input file. While other cases took HyperScan just a few milliseconds, here, it took much longer to go through all of them. But in general, the HyperScan provides impressive speed in most cases.

Conclusion

There are several pattern-matching engines, many of which have much potential for fast scanning. Of course, many of them profile for a specific use and not all of them can match multiple patterns simultaneously or scan behavioral reports.

To be clear, this post is not about criticizing Yara or any other engine. It is rather about testing available options and thinking about the possibilities for how to improve what we already have.

As I mentioned before, my team is planning to release some exciting projects in the near future that were inspired by similar tests, so stay tuned for more.